Know Your Role And Shut Your Mouth: How Video Games Helped Create A Culture Of Smarks

PHOTO WWE 2K17, BROCK LESNAR

Note: The following is an editorial submission by Liam Lambert. You can follow Liam on Twitter @Crowtagonist.

Tune in to today’s pro wrestling fandom, and one of the first words that springs to mind is ‘entitlement.’

Wrestling fans have become consumed with their idea of Monday Night RAW; their World Wrestling Entertainment. We live in a culture of ‘smarks’, connoisseurs of the squared circle who believe themselves to be above the art of professional wrestling itself. Rather than simply following storylines and enjoying matches, we now take to Twitter to complain about the art we supposedly love. We argue about booking directions in forums, make fun of title belt designs at live shows, and urge Vince McMahon to #CancelWWENetwork when ‘our guy’ loses.

Kayfabe has long been dead, and in its absence a new culture of participation and creative ownership has infected professional wrestling.

And it is incurable.

But the source of the disease can be traced back to a few important cultural shifts, shifts that exist both inside and outside of the pro-wrestling industry.

The first is the proliferation of online message boards and social media, internet soap boxes that allow fans to speculate about wrestling until they cannot speculate any further. Twitter and Facebook have instilled a belief in us that all ideas are equal, and must be shared and re-shared ad nauseam. This seems doubly true in the internet wrestling community (or IWC), the members of which regularly conform to opinions not necessarily of their own, through fear of resentment or exile from their fellow fans.

The second is, of course, Vince McMahon’s own demolition of kayfabe.

Back in 1989 when Vince declared wrestling was "an activity in which participants struggle hand-in-hand primarily for the purpose of providing entertainment to spectators rather than conducting a bona fide athletic contest,” he outed his own product as a ‘work’.

These days, a large percentage of WWE Network programming intentionally reveals the inner workings of professional wrestling, and although there are a few holdouts still clinging to kayfabe on WWE’s active roster, there are more performers sharing intimate behind-the-scenes stories of Twitter or on their personal podcasts.

The third shift is somewhat less obvious, but it’s no less integral to the 21st Century’s ‘smarksist revolution’.

Before I watched a single episode of RAW or Smackdown, I played a Smackdown video game with my best friend. I was instantly drawn in based on the fact that you could hit referees with chairs, something that was frowned upon in other sports.

Through creating these stories, and through playing out dream matches on subsequent wrestling video games, we slowly began our descent into the realms of fantasy booking.

The main selling point for WWE games since the mid-2000s has been customisability. Throughout the years, these games have allowed us to create wrestlers, title belts, arenas, entrances, video packages and even finishing moves, all to quench our thirsts for more ownership of the WWE product.

In many ways, WWE’s video games are majorly responsible for incepting this idea that ‘we can book it better'.

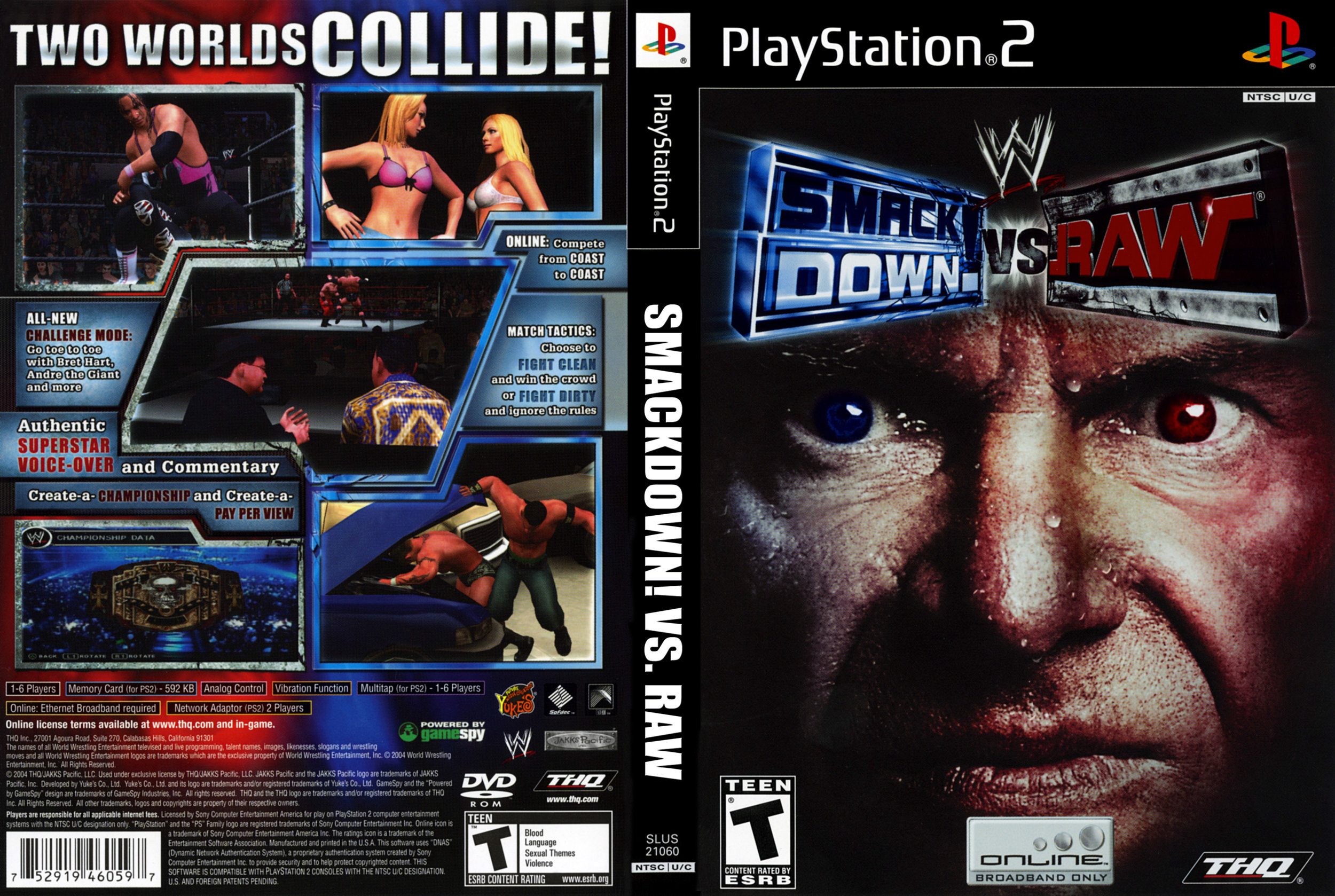

Smackdown vs Raw titles from the mid-to-late-2000s are particularly indicative of this. These games introduced ‘General Manager Mode’, a sort of lightweight Football Manager sim that allowed players to control a brand of their choosing. They could pick which Superstars they wanted on their roster, which angles would appear on particular parts of the card, and which segments would air on specific nights.

It was a fantastic mode, but it was near-impossible to win. You could have endless hours of fun conjuring madcap stories and building up wrestlers’ popularity, but your AI opponent would almost always win the ratings war - the mode’s barometer for success. You could maintain a consistently ‘good’ run of shows throughout the simulated year, but so long as the opposing brand put John Cena vs Hulk Hogan in the main event each week, they would always come out on top, even if the rest of their card was filled with one-star matches between ‘buried talent’.

Ironically, this felt like a knowing nod to WWE’s modern booking philosophy, and its relationship with fans. You can scream for AJ Styles vs Samoa Joe or Finn Balor vs Sami Zayn all you want, but WWE will put Brock Lesnar and Goldberg in the main event because that match will sell tickets.

General Manager Mode was eventually removed from WWE’s games, but the damage had already been done.

Because WWE has supported and provoked an environment of creative agency and ownership among their fans (they even ran a string of pay-per-views in the 2000s wherein fans could vote for opponents and match stipulations), they have cast themselves in a thankless role.

By allowing players to tell and experience their own stories, the WWE have created a perpetually dissatisfied fanbase who doesn’t think, but rather knows it could do a better job of booking WWE’s programming.

Even outside of these explicitly creative elements, having the ability to play or ‘book’ Finn Balor vs The Undertaker or Ricky Steamboat vs Luke Harper in exhibition matches has offered fans an unrealistic and impossible alternative to the WWE programming that exists in real life. So when WWE goes ahead and puts AJ Styles against Shane McMahon at WrestleMania, a large percentage of fans cry out.

The same situation never arose from Football Manager games or story modes in the NBA series, because football and basketball aren’t predetermined. Unlike wrestling, those sports cannot be altered by fan input or outside sources, and their fans know that.

We’re all guilty of this bastardization of ownership, and I don’t consider myself to be any different.

In many ways, wrestling and gaming are cut from the same cloth. Look closely at the cultures surrounding these industries, and you begin to see some uncanny parallels. Like wrestling, the games industry is trying to drag itself out of its own ‘Attitude Era’, a culture in which games were predominantly about jacked dudes firing big guns, and the only women to be featured were scantily clad damsels in need of rescue.

Duke Nukem Forever Wallpaper

The demographic similarities go without saying; both skew male, white, 18-35, middle class etc.

Perhaps something can be gleaned from this. Perhaps the ‘smark’ is just an offshoot of the ‘gamer’, and the culture of smarkiness in which we find ourselves is a result of the gamification of professional wrestling. No longer do we watch professional wrestling simply to be entertained by stories, we also watch it to participate, to engage in art both as viewer and creator.

These are the same whims and psychological ticks that fuel our desire to play video games.

VIA Mass Effect Andromeda - a 3rd-person action-adventure RPG where players assume the role of an intergalactic explorer. It is the forth entry in the popular Mass Effect series. The primary selling point of the series is its emphasis upon "player choice", creating a deeply immersive, interactive version of a "choose your own adventure novel".

Traditionally, games have always been power fantasies of some variety, ways to exert control over some distant, unreal world or being. When we play any game, it is to escape into something that we don’t see or experience in our everyday lives. It is to conquer powerful foes, explore exotic lands, befriend interesting people, and live out fantastic stories that are partly constructed by an author, and partly constructed by us, the player.

That’s how the modern fan approaches WWE; Braun Strowman isn’t a person or even a character in a story. Braun is a tool in our collective creative toolkit through which we can imagine our own stories. He’s an action figure, an avatar, a building block in Minecraft, or a dialogue option in The Witcher III.

VIA www.thewitcher.com - The Witcher III: The Wild Hunt is the third in a series of role-playing fantasy games based upon the short stories and novels of Polish writer Andrzej Sapkowski. It is widely regarded as one of the best, most immersive games of this current console generation. Players assume the role of monster hunter Geralt of Riveria, one of the last remaining Witchers (feared mutant warriors who are basically the Jedi Knights of their fictional universe). Players lose themselves in this highly detailed world, crafting their own experiences as they pick and chose which quests to venture on and how to interact with NPCs (non-playable characters).

Is the rise of ‘fantasy booking’ and the ‘fans know best’ mentality simply a manifestation of childish online behaviour (the sort of behaviour, interestingly, that came part and parcel with gaming’s so-called cultural revolution, ‘GamerGate’), or is it indicative of the way fans have been conditioned to think beyond the mat and behind the curtain of professional wrestling?

In reality, it’s a little of both.

Video games can’t take sole responsibility for this shift in wrestling fans’ behaviour, nor can Vince McMahon, the CEO of Twitter, nor even the fans themselves. It’s a change that was born of a collective desire to create, to have our say. It may not be manifesting itself in the right way, but like General Manager Mode or any other game that encourages independent creativity, this desire shows that fans are eager to manipulate or enhance the art they enjoy, even if they’re not yet totally comfortable in the way they do it.

WWE is not a company that should be let off the hook for its bad decisions. This is an incredibly wealthy organisation, one with its finger in a staggering amount of political and corporate pies. Like all art, professional wrestling should be critiqued and deconstructed, especially art created by a global corporation with unimaginable financial heft.

Kayfabe is dead, and we’re all wise to the work. But that doesn’t mean we couldn’t be wiser about the way we approach our criticism of the medium we love. As great game design teaches us: it’s not necessarily about what you’re doing, but how you’re doing it.

Currently, we’re trying to make our voices heard about the quality of WWE’s product and our dissatisfaction with its booking philosophies, but we’re going about it through snarky smarkiness, online screaming matches, and a sense of self-importance that can only come from the ultimate power fantasy.

We have been afforded great agency over professional wrestling, we just don’t know what to do with it.

Follow Liam Lambert on Twitter @Crowtagonist.

SUBSCRIBE TO WORK OF WRESTLING PODCAST