The Demise of the American Babyface

AN EDITORIAL SUBMISSION BY BARRY HESS - PHOTOS VIA WWE

Note: This article is by writer, pro-wrestling analyst, and Voices of Wrestling contributor Barry Hess.

Follow Barry on Twitter @BFHess171.

A prone Dolph Ziggler lay flat on his face in the middle of the ring.

He struggled to regain his bearings as Baron Corbin approached with a steel chair in hand. Having just earned a nefarious victory over ‘The Showoff’ wasn’t enough; the vitriolic fire in Corbin’s heart would continue to rage until the satisfactory pound of flesh was properly extricated from Ziggler’s battered physique. Luckily Kalisto, a previous victim of Corbin’s post-match antics, raced down the entrance ramp just in time to chase the cowardly heel away and save his friend from further violence.

This familiar pro wrestling scene took place on the first SmackDown Live of 2017 and came on the heels of a satisfying resurgence of Ziggler’s babyface character thanks to a compelling program with The Miz in the later stages of the previous year.

With the threat of danger removed Kalisto turned to check on Ziggler, who staggered back to his feet just in time to deliver a shocking superkick to the heroic luchador. The timing of the scene was impeccable; the performance of each of the players was flawless; the soundtrack of Mauro Ranallo’s shock and outrage framed the live action precisely as it should have. All the ingredients for a successful heel turn were present and accounted for. Yet, as I watched from the comfort of my living room a debilitating disconnect infected the proceedings and prevented me from absorbing the scene as intended.

As Ziggler stood overtop his unsuspecting ally, shouting vengeful rhetoric in true heel fashion, members of the audience rose to their feet and started to cheer. The cheers were dull at first, not unlike the kind of initial clamor exuded from a crowd whenever something unexpected takes place during a show. But as the heel turn became clear the dull cheers turned into a thunderous roar before a coordinated ‘Yes!’ chant was being bellowed from most every seat in the house. ‘What in the world is going on?’ I asked myself as I struggled to close the gap between what my eyes were seeing and my ears were hearing. ‘What is the audience seeing that I missed?” It didn’t make sense at all. Re-watching that same scene unfold six months later was an amazing experience; it was almost as if I was viewing it for the first time, or at least through a different lens that allows one to pick up on key factors that went previously unseen.

Pro wrestling, like other forms of art, is a product of its environment. The stories of the medium are most successful when they accurately reflect the reality of the society running parallel to a promotion’s fictional universe. A well-informed critic can sample any story from any promotion throughout any period in history and accurately articulate why it was successful or why it failed based, in large part, on how its’ psychology played against the reality of its time.

- FINDING A HERO -

When I was 10 years old I had four heroes; four male figures that influenced my life in a profound manner. Like many young boys, my father was my hero. My two grandfathers, who served in World War II and the Korean War respectively, were my heroes. I was connected to these men by blood. I lived with them. I was educated by them. I turned to them for comfort and guidance.

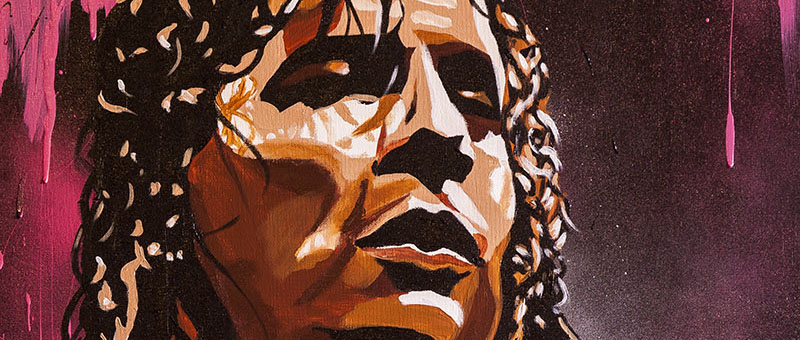

My fourth hero was Bret Hart, a pro wrestler from the World Wrestling Federation whom I had never met. Television was my only conduit to this hero, an incidental detail that hardly subdued my reverence for the pink and black-clad character. My relationship with Hart was forged by the quintessential magic of pro wrestling; psychological manipulation masked by an invisible kayfabe façade, a bond that proved equal in strength as one shaped by genetics.

I was first exposed to pro wrestling in the 1980s. Being born and raised in Philadelphia meant I was smack-dab in the middle of World Wrestling Federation territory during the height of Hulk-a-Mania. Unlike the majority of pro wrestling fans of that era, especially those in my age demographic, I was not a Hulk Hogan guy (or kid as it were). Looking back on those formative years, I can say with some degree of certainty that the younger version of me simply refused to buy-in to Hogan’s character. I didn’t support his mantras. I didn’t trust his motivations to be true. I didn’t believe in the professed power of Hulk-a-Mania. Perhaps it was some combination of my socio-economic status and the rough influences of my early life that prevented me from subscribing to the wholesome tenets of Hulk-a-Mania.

Perhaps it was a subconscious desire to separate myself from the masses. Whatever the reason, my lack of connection to Hogan naturally drew me to his rivals, colorful heels like Roddy Piper, Andre ‘The Giant’, King Kong Bundy and Randy Savage. I knew these characters had villainous intensions. Even at a young age I understood that their evil ways would ultimately lead to their downfall. I didn’t care. Larger than life conflicts, lively promos, the explosion of color and sound, unbridled physicality; those were the features - not a connection to a particular hero figure – that initially hooked me to the product. I spent the first five years of my fandom without a hero. Sure, I cheered for protagonists like Ultimate Warrior, Ricky Steamboat, Demolition and others, but their success had no substantial influence on my viewing experience. Essentially I had no skin in the game. I was playing with house money every time I tuned in…until 1992.

I didn’t know it at the time, but watching Bret Hart lose the Intercontinental title to his brother-in-law, The British Bulldog, in their graceful match at Summer Slam 1992 changed the way I absorbed pro wrestling forever. There was something there; something intangible that I couldn’t process or articulate at the time. Something about the way Hart entered Wembley Stadium; something about the way he refused to accept the role of an underdog even as his opponent enjoyed overwhelming support from the sea of humanity watching live; something about the way he conducted himself in defeat.

That indescribable something stuck with me for the better part of a year, subconsciously building with each passing month. In June of 1993 Hart would be crowned the winner of the King of the Ring event, winning three matches against three different opponents in the process. Taking that arduous journey with him as he progressed through the brackets that night finally made it all clear. I was no longer simply an ambivalent observer. For the first time I was actively rooting for a desired outcome; I was emotionally invested in Hart’s success. And upon achieving that success, some part of his victory became my victory as well. It was as if we achieved something together. From that moment on I wasn’t tuning in to watch wrestling, I was tuning in to watch Bret Hart. ‘The Hitman’ was my first pro wrestling hero and the day that became a conscious realization was a transformative event in my bourgeoning pro wrestling fandom.

Bret Hart was perhaps the most unique character to ever be anointed the top babyface of Vince McMahon’s universe. Hart’s primary characteristic was the fact that he was a talented wrestler. That’s it. Sure, there were traditional pro wrestling conflict devices inserted into many of Hart’s stories (like the feuds with his brother, Owen Hart or Jerry ‘The King’ Lawler) but Hart’s status as a superior athlete – The Excellence of Execution - was the preeminent theme of his 5 year run as the top babyface of the promotion. He was not a larger than life superstar. He was not a melodramatic sports entertainer. He was a championship caliber wrestler, who conducted himself as such. Hart’s wrestling ability (and the personality traits derived from that ability) was what ultimately drew me to the character and motivated me to invest in his success.

Such an investment has traditionally been the keystone of successful pro wrestling storytelling over the course of the last century.

While the industry has undergone numerous transformations over those decades the primary reliance of babyface characters has remained the same since Frank Gotch and George Hackenschmidt headlined the first substantive American wrestling event in 1908. Of course babyfaces can come in all different shapes and sizes. Infallible supreme heroes like Bruno Sammartino, Hogan or John Cena; common man heroes like Dusty Rhodes, Steamboat or Tommy Dreamer; underdog heroes like Daniel Bryan, Mick Foley or Bayley; fiery heroes like Steve Austin; flashy heroes like Sting; native son heroes like Kerry Von Erich. These themes and others like them have held true despite countless shifts in both substance and presentation respectively.

Until now, that is.

- A NEW WORLD -

A quick scan of the current American pro wrestling landscape (not just WWE) paints a vivid picture, especially when compared against what the industry looked and felt like just a few short years ago. The stark differences in today’s pro wrestling, both in terms of character development and the manner which the audience responds to that development, is eerily similar to a monumental shift that transformed Hollywood almost four decades ago.

For the longest time the Western was the preeminent genre of American cinema, mainly because of the compelling protagonists at the center of the stories. Gritty characters, often played by John Wayne, Gary Cooper or others of similar stature, who unwillingly assumed the hero’s role; figures who acted out of a self-imposed obligation to do the right thing rather than for the glory of victory or a heightened sense of self-importance; brave characters, who traversed the dangerous plains of the great unknown for the advancement of their communities; honest characters, who could be trusted to preserve law and order in a time of few laws and even less order. These characters were the embodiment of The Greatest Generation and the values they stood for in a post-World War II America.

In the 1960s and 70s, however, a new generation had begun redefining what values were important in America.

By the time I was born in 1983, thoughtful considerations and measured expectations were replaced with unbridled displays of self-expression and unapologetic acts of self-preservation. Traditional themes like loyalty and modesty were replaced in favor of themes like power and wealth. It was during this period that the American Western became passé almost overnight; eroding within the brisk winds of change and replaced with a new genre, American Crime. Irreverent gangsters who ignored established rule of law in favor of parochial codes created to benefit the strong and eradicate the weak; fast-living characters, who took as much as they could as fast as they could without fear or consideration of the consequences; ruthless lords of America’s underbelly positioned as defiant anti-heroes. These characters became the new standard-bearer of American cinema in successful films like Scarface, Once Upon a Time in America, Harlem Nights, Wall Street, Goodfellas and others like them.

We are now in the throes of yet another shift in American culture; a disturbing period that has the danger of becoming more of a cultural regression than evolution.

America is a nation currently devoid of undeniable heroes and is instead populated with those who temporarily achieve hero status only to prove unworthy of such a title down the road. In this new America, like Gotham City at the conclusion of The Dark Knight, you either die a hero or live long enough to become a villain.

Once beloved celebrities like Bill Cosby, admired athletes like Tiger Woods and, of course, entrusted public officials and politicians prove to cast dark shadows when exposed to the intense light of the information age. No one is far from the proverbial heel turn anymore. Worse still, we as a collective society have not only learned to accept this troubling fact, but we have come to expect it.

Pro-wrestling was one of the last remaining industries to become infected by this unmistakable shift - ironic considering long-standing criticisms about the unsophisticated nature of the product – most likely due to the invariable formulaic nature of its storytelling and the audience’s unwillingness to question that formula. American pro wrestling may have withstood the initial barrage of this cultural shift in ways Hollywood and other industries could not, but this cultural osmosis of sorts could not ultimately be prevented.

American babyfaces are now viewed with the same probing scrutiny as real would-be heroes of our time. Supreme hero character-types are no longer viewed as infallible cradles of justice, but rather a source for resentment and mistrust. Everyman heroes and underdog characters, like those of the American Western, go from inspiring to cliché at an unprecedented pace. Heel turns are no longer shocking devices to generate heat (like Hogan’s infamous NWO turn in 1996), but welcome manifestations of a character’s inner malice perceived by the audience to exist all along (like Kevin Owen’s betrayal during the Festival of Friendship).

The modern day American babyface has proven incapable of surviving in the creative petri dish of kayfabe conflict and inescapable reality for any substantial period of time; a fact easily proven by the lack of a standout babyface currently performing in any American promotion.

Yes, this goes far beyond WWE’s current Roman Reigns problem. The biggest non-WWE attraction in the industry is currently The Bullet Club, an ever-evolving stable of heels headlined by super-popular heel tag team, The Young Bucks. Other non-WWE characters, like Marty Scurll (whose nickname is literally ‘The Villain’) receive the full backing of the audience while traditional babyface characters must work twice as hard to sustain half the adulation. In WWE monster heels like Brock Lesnar and Braun Strowman, arrogant heels like the 2016 version of AJ Styles or bully characters like Kevin Owens are routinely more popular than their babyface counterparts.

This curious embrace of heel characters is worthy of an investigation all its own. Whatever psychological factors are at play must be identified by the puppeteers who control the fictional narratives of the product. Adjustments to both character types are essential if the industry is to enjoy the creative balance in which it was founded. Perhaps the heel of the future is a transparent con artist in disguise. Perhaps the level of villainous behavior must be taken to new levels not yet considered. If the current face/heel dynamic remains uncalibrated then the entirety of the American audience could eventually be comprised of ambivalent versions of my 8-year old self emotionlessly watching Hulk-a-Mania run wild.

In the debut episode of The Sopranos, Tony Soprano openly wonders ‘Whatever happened to the Gary Cooper, the strong, silent type? That was an American.’ as he rejects the idea of therapy as a tool to identify aspects of his past responsible for debilitating anxiety and depression.

The reference was a clear metaphor for the swift disappearance of the American Western and the genre’s classic protagonists.

It would be a real shame if American pro wrestling fans of the future began to question, “Whatever happened to Bret Hart, the Excellence of Execution? That was a babyface."

ART BY @ROBSCHAMBERGER

Follow Barry Hess on Twitter @BFHess171.