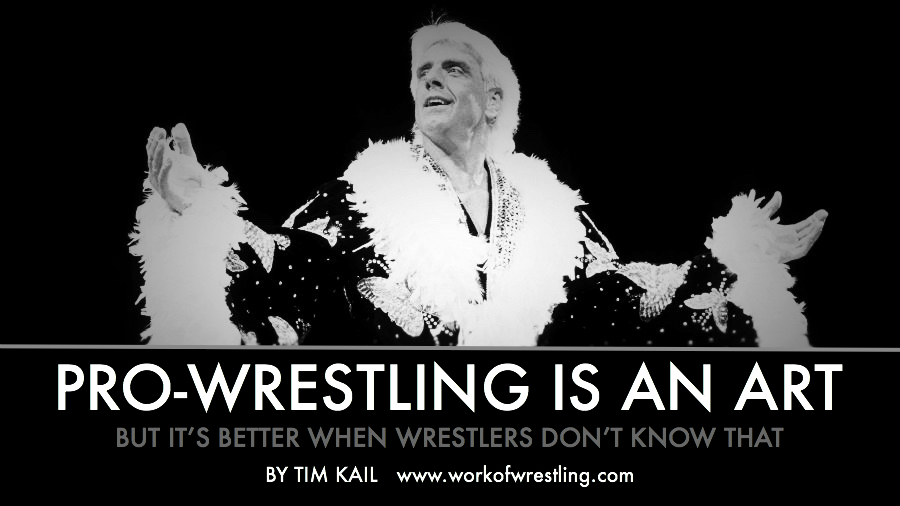

Pro-Wrestling Is An Art...But It's Better When Wrestlers Don't Know That

PRO-WRESTLING IS AN ART BUT IT'S BETTER WHEN WRESTLERS DON'T KNOW THAT

Editorial by Tim Kail

- INTRODUCTION -

Professional wrestling is an art.

That's the simple truth.

Proving and reinforcing that truth with my style of pro-wrestling-arts-criticism has always been the purpose of my writing and my podcast. It is an accurate way of analyzing the medium that quickly dismantles the age-old claim "wrestling is fake", and simultaneously positions pro-wrestling to be watched (and created) with the respect it deserves.

The idea that pro-wrestling is an art is by no means new: philosopher Roland Barthes wrote about wrestling as theater in the 1950s, Bret Hart stated with his trademark tempered pride, "There is an art to wrestling" in the 1998 documentary Wrestling With Shadows, and CM Punk told GQ in 2011, "It's truly, I believe, one of the only art forms that America has actually given to the world, besides jazz and comic books".

CM Punk, WWE Champion

Such perspectives have always represented outliers to the norm, though, even within the pro-wrestling community itself. Pro-wrestling is traditionally thought of as "sideshow" or "soap opera for men" or "entertainment" or "fun" or it's true meaning and nature isn't even thought about at all. It's just a low-brow kids show residing in the discount DVD bin of the pop-culture consciousness somewhere between Rocky III, Jerry Springer, and American Gladiators.

But the "pro-wrestling is an art" thesis has gained more and more momentum in recent years thanks, in part, to the proliferation of social media. I've watched and listened, from 2014 to today, as the idea "pro-wrestling is an art" has become demonstrably more commonplace within the community and beyond.

More and more wrestlers are comfortable talking about "their art" and their desire to earn "creative freedom" on podcasts. Shinsuke Nakamura has been dubbed "The Artist Known As..." by SmackDown Live Commentators. Jim Ross referred to professional wrestling as a "medium" at New Japan's G1 USA Tournament. Ricochet defended his widely criticized and widely lauded 2016 New Japan match against Will Ospreay by releasing the following statement on Twitter:

People don’t understand that “professional wrestling” is an art. And much like ANY art, there are endless ways to express it. It can LITERALLY be anything the performers in the ring want it to be...

And just last week The New York Times, which has more subscribers digitally and in print than it has ever had in its 164-year history, published The Aria Of Babyface Cauliflower Brown, a short documentary that explains through a combination of imagery and voice-over why professional wrestling is art.

"Skip the Opera, Go See Some Pro-Wrestling" the headline reads. More people may see that headline than will watch Monday Night Raw live.

Right now, professional wrestling exists in a conceptually awkward space comparable to adolescence. The art itself has come out of its childhood (representing the past 80 years where kayfabe reigned over an "innocent" and "naive" fandom) and within the past twenty years it has entered a more self-aware, self-critical phase. This is often one of (if not the most) difficult stages in a life-cycle.

When we're adolescents, subversive ideas are like shiny new toys. They captivate us and shield us, even if we don't fully understand their implications. A phrase like "pro-wrestling is an art" is tantalizing to pro-wrestling fans and pro-wrestlers today because we have a sense that it accurately articulates our love and respect for the medium.

The word "art" carries appropriate heft, and so it allows fans to proclaim their truth with the same "damn the man" veracity as a teen recently awakened to the perils of "the system".

All of this can be beneficial in the long-term; a necessary step toward deeper enlightenment. But we must proceed with some caution. Remember, adolescents are impressionable and prone to being steered in the wrong direction.

The popularization of the idea "pro-wrestling is an art" may have some unintended, adverse effects that could blossom into bigger problems in the future. We must not unwittingly create yet another era of misunderstanding just because we've found a new way of articulating our love of pro-wrestling.

So how exactly could this expanding consciousness go wrong?

To answer that question, we must first understand what art actually is, and then we must understand what, specifically, makes pro-wrestling an art.

- THAT WHICH ISN'T, NOW IS -

"Pro-wrestling is a sport is the most fundamental story that a pro-wrestling match tells..."

Bret Hart - WWF Champion

The word "art" doesn't mean, "I really, really like this thing and so I'm going to use a really important adjective to describe it".

And yet that's often how the word "art" is used. People understand that "art" is associated with intellectualism and quality. So, when they recognize that something they like ascends to a higher level of excellence, they call it "art" even if that thing they like isn't actually an art.

This is a misuse of the word born out of a misunderstanding of what art is. Art is not just a "higher form" of something else. This is the same misunderstanding that leads to elitism in our culture.

All arts are defined by the specific way they execute a particular illusion. That's it. The crux of what makes something art is how it takes something that isn't and makes it appear as though it is.

Film creates the illusion of motion through a series of still images projected in rapid succession. Play's create the illusion of a moment in life by rounding out a scene with characters, dialogue, and a setting. Novels create the illusion of an existing world in the reader's mind through descriptive writing, dialogue, and, occasionally, pictures. Music creates the illusion of emotion, consciousness, and history through the manipulation of sound by voice or instrument. Paintings & sketches create the illusion of whatever they are depicting - whether that is a tangible space or object, or an intangible emotion, thought, or memory - through various paints, oils, chalks, papers, or skins.

The various ways different artists approach creating the illusion of their chosen medium is what gives birth to new styles and new disciplines within that particular medium. Oftentimes, when artists think up a new style, they must also invent new techniques & new technology to realize their vision. This is how we arrive at innovation in the arts.

Think about all of your favorite arts in this way and you will forge a deeper understanding of them.

Ask of your favorite art, "What illusion are you performing?"

If we ask that of pro-wrestling, the answer is clear:

Professional wrestling creates the illusion of sport.

That is the foundation of pro-wrestling. This is easily forgotten or, worse yet, easily never learned

Roddy Piper vs Bret Hart

Professional wrestling is so mired in negative perceptions that people tend not to think about, let alone theorize about, the inner-workings of the medium. And even on pro-wrestling's best day it's usually wrapped in fireworks and melodrama, distracting everyone from its true nature.

Fans may say the phrase "Pro-wrestling is an art!" just because they appreciate the spectacle of pyrotechnics, the craftsmanship of costumes, the eloquence of a wrestler's promo, the majestic athleticism displayed in a match, or the complexity of a booking decision.

That understanding of what makes pro-wrestling an art is, very simply, wrong.

The art of pro-wrestling is not in acrobatics, styles, promos, vignettes, costumes, angles, or gimmicks. Those are elements of the medium, and they do not constitute the art itself.

The art of pro-wrestling is in making the simulation of combat appear real. It's in making people believe something that's not real is real while adding narrative to that deception.

That is what makes pro-wrestling an art.

That's "the work" of wrestling.

Sasha Banks vs Charlotte in NXT

"Pro-wrestling is a sport" is the most fundamental story that a pro-wrestling match tells and if it's not, in any way, telling that story then it's not being pro-wrestling.

The ring, the fact that the performers are called "wrestlers", the presence of commentators, and the setting all exist to reinforce the illusion that what the audience witnesses is exactly what it says it is; a fight. Pro-wrestling is an exaggeration of a fight, of course. Sometimes it defies logic and physics. Sometimes it's silly and funny. But all art is an exaggeration of life.

So long as the performance of pro-wrestling remains rooted, no matter how extravagant, far-fetched, or absurd, in the principle that it is simulating a fight, pro-wrestling is still being pro-wrestling.

The word "fight" in that last sentence could mean many things. It could mean a fight that's portrayed through literal punches and kicks or a fight that's portrayed in a flurry of acrobatic one-upsmanship. No one style undermines pro-wrestling more than the other. The only creative choice that truly undermines pro-wrestling is the one that freely admits a wrestling match is staged.

To grasp why this is, we must better understand the concept of kayfabe and how it established the artistry of pro-wrestling.

- THE BLESSING & THE CURSE OF KAYFABE -

"Kayfabe was the foundation of the business for so long that it inadvertently established the art of pro-wrestling as being the simulation of sport..."

Ric Flair

Boiled down to its simplest form, kayfabe means "staying in character". But that doesn't quite do the phrase justice. Kayfabe is bigger than just the individual wrestler and their willingness (or unwillingness) to maintain their fiction. Kayfabe takes the concept of "staying in character" to such a literal extreme that it becomes difficult not just for the fan to distinguish between real and unreal or "shoot" and "work", but for the wrestler, and for the art of wrestling itself to distinguish between "shoot" and "work".

There was a time when pro-wrestling portrayed itself as a legitimate sport, and pro-wrestlers refused to compromise that fiction (or "break kayfabe"). Stories pass through the generations of wrestlers getting in legitimate "shoot" fights with fans who didn't believe them or who challenged their toughness. Rivals rode in separate cars to ensure fans would never see them together and get wise to "the work". Practices such as these are commonly described as "protecting the business".

The need to "protect the business" was directly related to pro-wrestling's ability to draw an audience. If the crowd didn't buy-in emotionally to the theatrics in the ring and believe what they were seeing, then they may not buy-in financially.

Rocky Johnson

In the age of kayfabe, the commitment of the wrestlers, and the business's focus on believability, inspired a similar degree of conviction in the fans. Some fans certainly knew "something was going on", but any doubt or suspicion about pro-wrestling's legitimacy was easily dismissed because the emotions that heels and babyfaces inspired were undeniably real. Not only did fans have a hard time distinguishing between fact and fiction, they didn't really care to. There was no Twitter or Facebook providing them an instantaneous feedback loop of rumors, spoilers, opinions, and leaks. Certainly there were "dirt sheets" and naysayers who helped expose aspects of the business to a wider public. But the average wrestling fan was happily in the dark about "the work". This naiveté manifested in a sincere (sometimes violent) hatred of heel wrestlers, and a profound, BeetleMania-like adoration of babyface wrestlers.

Kayfabe was the foundation of the business for so long that it inadvertently established the art of pro-wrestling as being the simulation of sport. Like most arts, pro-wrestling wasn't actually conceived as an art. The medium's status as what we typically regard as "art" is the result of an hundred years of continuous evolution from the "step right up, folks!" days of manipulating carnival "marks" to the annual extravaganza we know as WrestleMania. The simulation advanced beyond a mere circus ruse; incorporating narrative and theatrical technique, thereby reinventing wrestling into a legitimate form of theater.

Roddy Piper

Unlike other forms, pro-wrestling is an art that functions best when the lines between reality and fiction are so thoroughly blurred that wrestlers start to "live the gimmick" (a phrase often used to describe wrestlers like Ric Flair who did not appear to make a distinction between the character he played in wrestling matches and the person he was in real life).

For Kayfabe to really work though, it is required that the wrestling promotion, the wrestlers, and the fans all agree, simultaneously, that pro-wrestling is a legitimate sport.

And that's where kayfabe gets conceptually dicey. People inevitably figure out that pro-wrestling is not what it says it is. After people learn that pro-wrestling is not a sport they can choose to either dismiss it or emotionally invest in it the same way they emotionally invest in other forms of theater. Promotions can decide to double-down on the idea of kayfabe and ignore the "smarter" fanbase, or promotions can embrace the death of kayfabe and open up the truth of their business.

Vince McMahon

Professional wrestling, even after the death of kayfabe, is still fundamentally different than other forms of theater though.

If pro-wrestling is approached, both by those creating it and by those watching it, in the same way one approaches movies or plays simply because traditional kayfabe no longer exists, then one has made a grave mistake. That approach misunderstands the innovate style of theater pro-wrestling represents.

It is important that we understand exactly how pro-wrestling is different than other forms of theater if we're going to avoid making this mistake.

- THERE IS NO WALL -

"Imagine a play that's not taking place on a stage but in the actual location described in the script..."

The Rock

Pro-wrestling is an art which cannot acknowledge that it is an art if it wants to properly execute its art.

This is what makes professional wrestling so unique in the pantheon of theatrical forms. Unlike other forms of theater, if pro-wrestling breaks its forth wall it ceases to be itself. In fact, professional wrestling is a form of theater that is so fundamentally different than other forms that the term "forth wall" fails to adequately describe what pro-wrestling is actually trying to accomplish.

The forth wall is a theater-term used to describe the conceptual barrier between a performance and the audience. For example, when you watch a play or a sitcom filmed before a live studio audience, you typically see the back wall, the right wall, and the left wall of an apartment where the characters are interacting. The forth wall is that imagined wall that must exist for the characters, but that doesn't literally exist for you, the viewer. If that wall did exist, you literally wouldn't be able to see the play.

The Globe Theatre

Professional wrestling, unlike a play, has no walls to begin with.

Let's use the phrase No-Wall-Theater then to describe a category of performance art that strives to mimic reality so thoroughly that it removes even the slightest appearance of artifice.

Imagine a play that's taking place not on a stage but in the actual location described in the script and you, the audience, are simultaneously characters in the play you're observing.

That's No-Wall-Theater, and that's what pro-wrestling is doing.

John Cena with the fans.

Movies and television are projected on a screen and so there is an obvious separation between the real and the unreal as they are executing their art. Plays similarly take place at a distance and within a three-walled box. Videogames, books, music, sculpture, painting all reside in literal spaces that are distinguishable from reality.

This distance gives such mediums the freedom to acknowledge that they are forms of art without destroying the illusion they're attempting to create. This is because the illusion they're attempting to create isn't that they are indistinguishable from reality. The distance between reality and the art is so well-established (and literally recognizable), it is obvious to the observer that these mediums are not reality. And there was never a time when film, television, and the like ever suggested they were reality.

Pro-wrestling, on the other hand, did at one time insist it was completely real. And, even to this day, pro-wrestling has all of the visual and thematic trappings of a legitimate sport. The wrestling ring is indistinguishable from a boxing ring to the layperson. Matches take place inside the same arenas and halls of legitimate athletic events.

Pro-wrestling calls itself "pro-wrestling".

Samoa Joe (left), Brock Lesnar (right)

The name of the medium itself is an essential part of its art. The use of the word "professional" suggests that it is, in fact, the highest tier in the legitimate sport of wrestling. Even if you know that's not true, you still must call it "professional wrestling", inevitably helping to tell the story that the medium strives to tell.

The people who perform in wrestling matches are not called "actors". They are called wrestlers.

No other popular art, save perhaps comedy and magic, lacks a language that distinguishes between the real-world artist and the medium they're performing in.

If a promotion or a pro-wrestler doesn't actually understand this they will unwittingly destroy the artistry of professional wrestling. If a promotion or a pro-wrestler does understand this then they will more effectively manipulate their audience and excel in their craft.

Jake "The Snake" Roberts

At this moment in pro-wrestling's history, it is unclear which direction the medium is going. This lack of clarity is the result of this conceptual discussion not being had often enough. The phrase "pro-wrestling is an art" is entering the consciousness of wrestlers and fans, and it is a phrase that will inevitably inform the way pro-wrestling is made and watched.

If the true meaning of that phrase (which must incorporate the illusion of sport and the fact that pro-wrestling is No-Walls-Theater) is not adequately processed, a new conceptual Pandora's Box will be opened and I'm not sure it will ever be closed.

What happens to the art of pro-wrestling when a wrestler knows wrestling is art?

- HOW TO NOT DO SOMETHING BY DOING IT -

"Art is work. Tangible, hard, blood-boiling work..."

Ricochet (left), Will Ospreay (right)

As previously mentioned, Ricochet, the man, Tweeted in response to criticisms of his dancerly, acrobatic style that pro-wrestling is an art and that it can literally be whatever the wrestlers want it to be. This is exactly the kind of statement enthusiastic artists make about their craft when they're attempting to share their expanded consciousness with others. People will read his statement and either think, "Yeah!" in fist-pumping agreement or they will roll their eyes in steadfast denial.

Typically, the young will be in agreement and the veterans will be in denial. This happens in every art.

The heart of the young artist is in the right place when they make such grandiose claims. There is even some accuracy in their words. But such statements are typically not fully formed thoughts. Often whenever artists claim that their art can "be anything", what they're really saying is they want cart blanche, and that they disagree with the criticisms they're receiving.

I know this, because I've done this.

Many times.

I would hear constructive criticism of my writing or short films, and then immediately rush to my work's defense. I would make grande proclamations of my own rightness in my own honor on behalf of the greatness of art. You see, I really understood what I was doing, and my work was indicative of true excellence in the craft. So how could I be wrong?! They were wrong! They just didn't "get it"...man!

If I was ever told "there are rules", I would make it my business to break those rules.

Eventually, I grew out of that short-sighted perspective and gained a deeper appreciation for my craft. I became a less selfish artist. I learned that art is not some ever-malleable play-thing that exists purely to satisfy my every whim. I realized that I had a responsibility to the art itself. I had to exist for writing as much as writing existed for me.

I found out that art isn't just "anything".

Art is work. Tangible, hard, blood-boiling work. And to understand how to do that work the artist must understand how to properly use the tools of their chosen art. The artist must trust that those tools were forged in the fires of diligent geniuses who came before, and then figure out a way to do it better.

I have no doubt that Ricochet understands this. I've seen and admired his work, and I find it eminently believable. My concern is that comments like "pro-wrestling can literally be anything" will enter the zeitgeist without context, and future wrestlers may genuinely end up believing, in the truest sense of the word "anything", that pro-wrestling can be "anything".

The beauty of an art is not that it can "be anything".

The beauty of an art is what it specifically does.

Pro-wrestling can do a lot of things. Pro-wrestling can be interpreted in many ways; from Bret Hart's athletic realism to Ricochet's parkour acrombatics.

Both are effective styles. Both are examples of the pinnacle of their individual perspectives.

But pro-wrestling cannot, and must not, allow itself to be "literally anything". If it does that, then that means there could be a "style of pro-wrestling" that admits pro-wrestling is staged.

A style of pro-wrestling that admits pro-wrestling is staged is simply not being pro-wrestling. Ironically, a pro-wrestler is only not performing the art of pro-wrestling when they're admitting that they're performing the art of pro-wrestling.

Re-phased for clarity's sake: professional wrestling is not professional wrestling when it's not sincerely simulating a competition.

When Ricochet, the wrestler (or "the character"), was wrestling Will Ospreay, was he thinking, "I'm making great art" or was he thinking, "I need to beat Will Ospreay"?

It seems to me like the character was thinking "I need to beat Will Ospreay" or "I need to outshine Will Ospreay", and that's good. That's still pro-wrestling. But what happens if that sense of competition completely disappears from the medium? What if it's not about a fight, but about the quality of a performance within the actual fiction of pro-wrestling?

Does the performer make the necessary distinction between his real-world understanding of pro-wrestling as an art and his character's understanding of pro-wrestling?

Ricochet (left), Will Ospreay (right)

If not, does that mean the character also thinks he's an artist simulating combat for the sake of eliciting emotional reactions? If that's the case, what does it mean when he "wins" or "loses" a match? Why is there even a referee? What is pro-wrestling if it is no longer trying to tell the story of competition when telling the story of competition is what makes pro-wrestling the art of pro-wrestling?

If the motivation of the wrestling character isn't to win then that means they just need to put on a "good match" in order to be "victorious". That means there is no distinction between the character and the performer.

That lack of a distinction between character and performer worked perfectly fine in the age of kayfabe when a wrestler like Ric Flair genuinely thought of pro-wrestling as a sport. But in a post-kayfabe age where a performer thinks of pro-wrestling as an art and simultaneously makes no distinction between themselves and their character, that performer is failing to actually do pro-wrestling.

Performing pro-wrestling openly as art doesn't actually tell the audience a story; it just tells the audience to smile at big, athletic moves. "Pro-wrestling is an art" practiced in the actual fiction of pro-wrestling is a less complex perspective. It is a point of view that relies more heavily upon the superficial beauty of high-spots. Being incredibly "acrobatic" becomes tantamount to "being a great artist", and that's just not true of the actual art of professional wrestling.

Andre The Giant (left), Hulk Hogan (right)

Being acrobatically gifted could certainly help someone be a better pro-wrestling artist, but that is not necessarily essential. Being able to convince the viewer that a move has legitimately caused pain is tantamount to good pro-wrestling artistry.

This understanding matters because any artist who proceeds into their chosen medium without a firm grasp on the basic tenets of that medium is going to be led astray and not fully capitalize on their talent. They're also going to misinform their audience. It's only when an artist truly understands their medium that they're able to bend it to their will as a master does. The pro-wrestler of the future who understands pro-wrestling is an art must also know that the art of pro-wrestling is contained within their ability to effectively hide the fact that they know pro-wrestling is an art.

Kayfabe made all of this a lot easier. It was like accidental method acting. Now, pro-wrestlers are going to have to engage in purposeful method acting if they want to be true to their art.

- TOMORROW AND TOMORROW AND TOMORROW -

"Pro-wrestlers of the future will need to consciously make that firm distinction between their real-world understanding of pro-wrestling as art and their character's understanding of pro-wrestling."

Kenny Omega (top), Okada (below)

Tomorrow's wrestlers have a more complicated mental space to navigate. They will have grown up knowing pro-wrestling as "a form of entertainment" or "an art", and not as "a sport". And so when they perform it, they will be likelier to perform it as "entertainment" or "as art" unless they've been taught otherwise.

The effect this could have on the art itself is that it could veer further and further away from authenticity. The art would be redefined by the superficial sound & fury of a show, not by the simulation of combat.

Traditionalists and critics argue that pro-wrestling has already lost that authenticity. I would argue that professional wrestling must allow for a variety of styles and interpretations from WWE's Disney-wrestling to Lucha Underground's mythological-wrestling to New Japan's sports-wrestling.

But I would also argue that regardless of the presentation or interpretation, pro-wrestling must maintain its most basic fiction; that a pro-wrestling match, itself, is real. That perspective allows for a lot of creativity, but it keeps the performance bound to the one and only defining aspect of its art. The responsibility of figuring out what all of this means for the future of professional wrestling lies with wrestlers and promoters.

Okada, IWGP Heavyweight Champion

It's not as though there is a Stanislavski method in the school of pro-wrestling performance art. There's "being in kayfabe", "getting over", "living the gimmick", "being yourself with the volume turned up", "reading from a script", "trying to make it look real", "trying to have fun out there", "making the people believe", and "putting smiles on faces".

This represents a confused, often contradictory methodology. There are too many conflicting perspectives on the "best way" to depict pro-wrestling without a single, core principle unifying all of them.

At least different schools of stage-theory agree that acting is acting regardless of how you do it. Some schools of pro-wrestling theory insist that pro-wrestling can be pro-wrestling even when it's not being pro-wrestling. This methodology must be streamlined so that the art can be practiced as effectively and powerfully as possible.

Achieving this can only be done if pro-wrestling purges itself of its insecurities. Many of pro-wrestlings writers and bookers throughout the years have approached pro-wrestling from the point of view that it needs to be something other than what it is in order for it to be successful.

It needs to be mini-movies. It needs to be Jerry Springer. It needs to be reality TV.

This point of view is not only disrespectful, it's wasting the art of pro-wrestling's time. And it is a point of view that has been proven wrong generation after generation. The art of pro-wrestling, which is the simulation of combat, always finds a way to come back to itself.

Even the WWE, which portrays itself as "entertainment", has found most success in recent years with narratives that rely more heavily upon a sports-realism perspective.

Pro-wrestlers, in the way they think about and practice that art, can help further along this return to the medium's core principles.

Brock Lesnar

Pro-wrestlers of the future will need to consciously make that firm distinction between their real-world understanding of pro-wrestling as art and their character's understanding of pro-wrestling.

In practice, this performer's mind would function in the following way: I know pro-wrestling is an art, but my character believes pro-wrestling is a sport.

Their character's perspective would inform their performance of the art, not the other way around. There would be no blurred lines there. The wrestling character would not be "fighting to entertain". The wrestling character would be "fighting to win".

It would then fall upon that pro-wrestler to decide how far they wanted to go with their character's point of view; will that wrestler be transparent in interviews and on social media about professional wrestling being an art or will they remain "in character" thereby extending that art.

"Broken" Matt Hardy

This is why the title of this article is "Pro-Wrestling Is An Art...But It's Better When Wrestlers Don't Know That".

The "wrestlers" I'm referring to in that title are the wrestling characters, not the wrestling performers. The performers can certainly know that pro-wrestling is an art. They can even talk about it as an art the way Bret Hart, CM Punk, and many others have in kayfabe-breaking interviews with the press.

But the characters of Bret Hart and CM Punk always thought of professional wrestling as a legitimate sport, and that's partially what made them great wrestlers. Even in CM Punk's "Shoot Heard Round The World" where he stated, "Whoops, I'm breaking the forth wall" he talked about pro-wrestling in realistic terms as a competition. His "Whoops" did the opposite of break the forth wall; it re-established the story of professional wrestling as a competition within the WWE.

Wrestlers like Hart & Punk understood that the portrayal of professional wrestling as an athletic competition, no matter how far-fetched it got, was the real art of pro-wrestling.

Promotions will have to similarly make a clear decision about how they want to portray professional wrestling. Waffling between "it's a fight" and "it's entertainment" (or "it's real" and "it's not real") does not yield positive results. Promotions must choose between embracing the No-Walls-Theater approach and consistently portraying professional wrestling as a legitimate sport or establishing a clear distinction between the reality of their business and the fiction of their stories.

As for future pro-wrestling fans, it's important that we not use the word "art" haphazardly.

We shouldn't call something an "art" just because we really, really like it. We should call something an art because that is an accurate description of what something is and what that something does. We should understand what we're saying when we say that.

Too often people call something "art" just because they want to seem intellectual or classy. If we go down that route as a community, we'll just continue to silo ourselves off from the rest of the world while simultaneously not really understanding what makes pro-wrestling an art in the first place.

CM Punk

- CONCLUSION -

Pro-wrestling is a medium still finding itself, which makes it a particularly fascinating subject of study.

Watching pro-wrestling evolve in real-time today is like journeying back in time to the early days of film and seeing the development of cameras, projectors, and sound design. This is why we should pay attention, and be careful not to misunderstand what we're seeing. The decisions we make now will shape what this art will be in the future.

Having beaten the "pro-wrestling is an art" drum for six years, the fact that this perspective is more commonplace today is heartening despite some of my concerns about the future. It's good that people are defending and celebrating pro-wrestling for what it is, and it's my hope that this will, within the next decade, translate into better wrestling.

While companies like the WWE have the most power at setting the bar for quality and cultivating a higher taste level in its audience, wrestling fans, critics, and indy promotions who refuse to accept low standards can help spur on change.

I'm excited to see how promotions of the future will behave & function after everyone (booker, wrestler, fan, and the media) all believe "pro-wrestling is an art, and that art is simulating sport".

Perhaps backstage segments won't be so poorly lit, poorly shot, poorly scripted, and poorly performed. Perhaps bigoted stereotypes and cartoonish gimmicks will finally be retired, usurped by nuanced, diverse, and believable characterizations. Perhaps the public will learn to respect professional wrestling in the same way the public already respects film and television.

We're not there yet.

But, one day, we will be.

We just have to keep trying.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA