The Road To Better Representation Of Asians At WrestleMania

Asuka of WWE - photos via WWE.com

Note: The following is a guest post by Daniel Lee. You can follow Daniel on Twitter @Lee_Daniel721.

On January 28th, 2018, two performers of Japanese descent, Shinsuke Nakamura and Asuka, won their respective Royal Rumble matches.

This was a defining moment, both in pro-wrestling history, and in my personal pro-wrestling fandom.

When you’re an ethnic minority, growing up a pro-wrestling fan presents a challenge.

Pro-Wrestling's xenophobic roots result in the medium's depiction of ethnic minorities as heels (villains) opposite "All-American", White, babyfaces (heroes). We are represented by racial caricatures and stereotypes that are designed to emphasize one’s foreignness. It’s a constant reminder that we are the “other”; that the way we look, the way we sound, the way we act inevitably elicits boos.

I was 10-years-old when Yokozuna (a Samoan-American portraying a Japanese sumo-wrestler) defeated Bret Hart at WrestleMania 9 to win the WWF Championship. Yokozuna was the unstoppable foreign monster, a 500-pound behemoth who crushed his foes with the deadly Banzai Drop.

Bret Hart was my favorite wrestler as a child, so I cheered when he used his guile and technical precision to lock Yokozuna in his Sharpshooter submission.

Mr. Fuji, a heel manager who’s aesthetic evolved from "Bond villain" to kimono-wearing-Japanese-flag-waving zealot, threw salt in Hart’s eyes. For a few short minutes, Yokozuna, an Asian character, was WWF Champion.

It could have been a moment that instilled pride in me, but I was overcome with shame.

Not only did he defeat my childhood hero, Bret Hart, but he did so by cheating.

So when Hulk Hogan came out for an impromptu match and proceeded to quickly dethrone Yokozuna, I didn’t have the “smart fan” reaction. I didn't see it as Hogan burying a younger talent. My 10-year-old self was relieved; filled with a sense that all was right with the world again.

Over in WCW, another Asian character was wreaking havoc on another one of my heroes. The Great Muta, a Japanese wrestler with ghoulish face paint and an exotic red veil, was the adversary of Sting, WCW’s All-American hero with blonde, spiked hair, tanned & toned physique, and red, white, and blue face paint.

I was too young to appreciate Muta’s “strong style”, the full contact martial arts strikes and the sharp snap in his movements, because his completely painted face and stoic expressions made him mysterious and unrelatable.

In the WCW/NJPW SuperShow 1991, Sting was attempting his signature Stinger Splash when Muta utilized the “Asian Mist”, spitting green liquid in Sting’s eyes to blind him and secure the win by nefarious means.

It was another reminder that Asians were regarded as devious and undeserving of sympathy. The deviation from that norm and, seemingly, the answer to my desire for Asian acceptance was Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat.

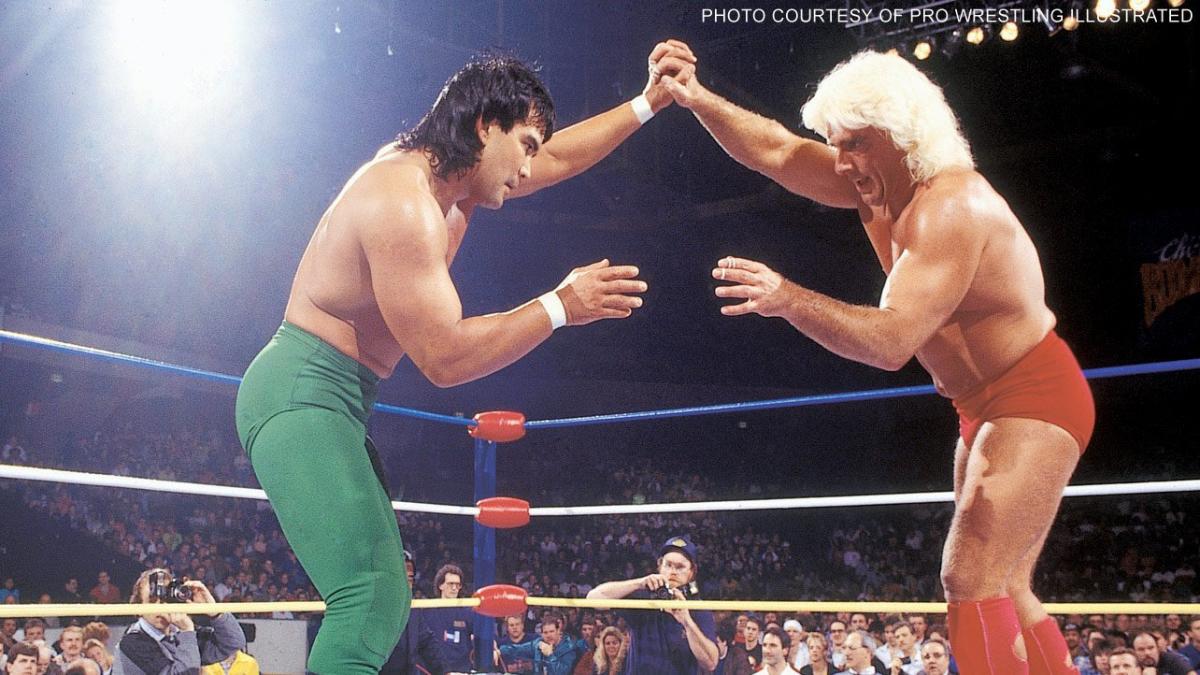

Ricky "The Dragon" Steamboat (left) vs "The Nature Boy" Ric Flair (right)

Steamboat was the prototypical babyface: a handsome, dynamic athlete whose ability to “sell” pain and “fire up” for heroic comebacks was nothing short of Shakespearian. His Intercontinental match with “Macho Man” Randy Savage at WrestleMania 3 is widely considered a masterpiece and one of the greatest matches WWF has ever produced. In addition, Steamboat had similar success in WCW, producing a brilliant trilogy of matches with Ric Flair for the NWA World Championship. This rivalry would set a standard for all wrestling feuds that followed.

What set Steamboat apart from other Asian performers was that he was allowed to be a hero.

During the “Golden Age” of WWF (1985-1992), Steamboat was only behind Hogan and the Ultimate Warrior in popularity as enduring babyfaces (characters who don’t switch back and forth from hero to villain). So why was Steamboat allowed to play the hero while performers like Yokozuna and Great Muta were villains?

Ricky "The Dragon" Steamboat

The secret to Steamboat was that he was an Asian not defined by his Asianness.

Despite the Keikogi martial arts uniform as part of his ring attire, and his use of knife-edged chops, he wasn’t another foreigner with a thick accent. His success in WWF and WCW echoed the childhood lessons I had received from my parents; that the key to acceptance was assimilation into mainstream morality and esthetic, that I should drop my accent and sound White.

The Attitude Era (1997-2002), widely regarded as the commercial and artistic peak of pro-wrestling, was simultaneously the low-point for Asian American characters.

Kai En Tai was a stable of Japanese wrestlers who debuted in WWF in 1998. They were immediately relegated to the lower-card, their most infamous feud being with Val Venis, a pornstar character who slept with the onscreen “wife” of manager Yamaguchi. This led to a TV segment where Yamaguchi brought out a salami and screamed “I choppy choppy your pee pee!”, a line that still haunts me to this day.

The line blatantly stereotypes Asian men as sexually inferior and deviant.

The story culminated with the members of Kai En Tai dragging Venis backstage where Yamaguchi attempted to chop off his penis with a samurai sword, only to be thwarted by John Wayne Bobbit.

Kai En Tai during "The Attitude Era"

After the Attitude Era, Asian representation continued to languish in ugly stereotypes.

Michinoku and Funaki wrestled in WWE as enhancement talent under the stereotype of dubbed English voices with badly lip-synced catchphrases.

Tajiri, a talented Cruiserweight, brought the same “strong style” strikes and Asian Mist that Great Muta had popularized. However, Tajiri sexually intimidated by All-American beauty Torrie Wilson, demeaned and subjugated her into wearing a geisha outfit.

Gail Kim, a Canadian-American of Korean descent, had everything to become the next Ricky Steamboat: a beautiful, fluent English-speaker who possessed an athletic, technical ring-style that outclassed most of her male peers.

However, she had the misfortune of being ahead of her time, a legitimate wrestler in a pre-“Women’s Revolution” WWE, where the company was more interested in sexualizing their female performers in bra & panties matches than in showcasing athletic prowess.

Kim moved on to TNA as the foundational performer of their Knockouts Division, becoming one of the biggest stars in the promotion’s history.

Gail Kim via Pro-Wrestling Wikia

In 2014, there seemed to be a renewed interest in Asian performers when WWE signed Japanese star Kenta, repackaging him as Hideo Itami. He was soon followed by superstars Asuka and Shinsuke Nakamura.

While I was initially excited that WWE was recruiting these global stars, my old fears took hold.

Would they be presented as racial stereotypes? Would they be accepted by the fans or would language barriers get in the way? Would they ascend to the top of the card or would they descend into Asian-minstrel gimmickry? Would anyone “get over” and find acceptance from an American audience?

From my own childhood, Asians were perceived as a homogeneous group: straight-A students, martial artists, asexual, and bad drivers.

When my peers discovered my interests ranged from hip-hop to creative writing, I was a cultural anomaly because I was breaking stereotype. Therefore, I was relieved that each performer was allowed to be themselves and embrace their Asianness.

Itami debuted in a yellow Keikogi uniform suggesting his martial arts background while his plain black tights signified that once the bell rang he would be a no nonsense badass. He was quickly positioned as a contender for the NXT Championship until a string of injuries derailed his momentum. Now that he has moved on from his injuries, Itami has been given new life on 205 Live.

Hideo Itami pinning Bryan Kendrick.

Asuka’s presentation couldn’t have been any better, communicating everything about her character from the outset.

Her various Noh masks signify her transformation from woman into a world-class fighter, “becoming” the mask just as a superhero would. Her multi-colored hair, vibrant kimono robes and ring gear are an allusion to Kabuki theatre.

Her exaggerated movements, vicious strikes, and submission holds instantly resonated with fans as they chanted “Asuka’s Gonna Kill You” at her opponents. She immediately emerged as a world-beater, becoming the longest reigning NXT Women’s Champion for 510 days. Asuka’s dominance and undefeated streak has only continued on RAW. It seems that WWE recognizes they have a once-in-a-generation talent in her.

Asuka makes her entrance.

As for Nakamura - he is one of the most unique showmen in all of professional wrestling.

Nakamura has transformed “strong style” into an artform, employing devastating knee-strikes, forearms, and kicks while simultaneously possessing the grace & fluidity of a ballet dancer. He has embraced the theatricality of pro-wrestling, channeling the showmanship of Michael Jackson and Freddie Mercury while he works.

He was booked like a special attraction in his NXT TakeOver: Dallas debut when the crowd sang along to his “The Rising Sun” theme song. That pop from the crowd during his dazzling entrance conveyed how “over” (popular with fans) Nakamura was before he even locked-up for the first time in a WWE ring.

Nakamura was the first two-time NXT Champion, and when he got drafted to SmackDown Live, emerged as a championship-contender within a few short months.

Regardless of wins and losses, I’ve been encouraged that Nakamura has remained near the top of the card.

The successes of Asuka and Nakamura paved the way for TJ Perkins (Filipino American) and Akira Tozawa (Japanese), two wrestlers who debuted in the Cruiserweight Classic, and later became fixtures on 205 Live. They have both held the WWE Cruiserweight Championship since their debuts.

Jinder Mahal, an Indo-Canadian wrestler who spent most of his WWE career in the undercard, took full advantage of a main event promotion in 2017, proving himself a worthy WWE Champion and deserved of future opportunities.

Kairi Sane (Japanese), the winner of the Mae Young Classic and new NXT star, has similarly benefited from this better representation.

Kairi Sane delivering her elbow drop.

So what are some of the reasons for the success of this recent group of Asian wrestlers?

Wrestling has never been more accessible, for one.

With sites like YouTube, NJPW World, ROH, etc. wrestlers can build a resumé and generate buzz before they enter the WWE.

WWE has also chosen to maintain, rather than erase, the histories of these performers, acknowledging in vignettes and on commentary most of their major accomplishments in other promotions. Debuting wrestlers are no longer unknown quantities.

Language has also not served as a significant barrier in their careers.

I was taught from an early age that the key to assimilation in America was English fluency. Especially for those performers from Japan, I feared that their accents would prevent fans from embracing them.

"Asuka needs an English mouthpiece!", and "Make Nakamura a Paul Heyman guy!", was the refrain of the pro-wrestling community.

These were the fears I had internalized. But I appreciate how the WWE has given these performers the opportunity to sink or swim on their own. They are allowed to cut promos on their own, even if the majority of their monologues are limited to a few short lines and familiar catchphrases.

Assimilation can operate as a two-way street: while the wrestlers work to improve their English, fans are tasked to become familiar with different dialects.

And, above all, Asia has become the new racial fetish in the pro-wrestling industry.

New Japan Pro-Wrestling is arguably the hottest promotion in pro-wrestling among diehard wrestling fans, and critically lauded by various wrestling journalists. Japanese wrestlers like Okada and Naito or the Bullet Club (a popular NJPW wrestling stable comprised of foreigners) represents "the exotic", a hip alternative to the Disney-wrestling offered by WWE.

In this sense, the Asianness of Asuka and Nakamura have worked in their favor.

They are the alternative to the more prototypical stars WWE has produced for years like John Cena, Randy Orton, and Brock Lesnar.

Is Asianness in pro-wrestling a temporary fad?

Will there be backlash when fans grow tired of Asuka’s dominance and Nakamura’s theatrics?

Probably so, because the nature of fandom is fickle. Moods change and what is en vogue today will be passé tomorrow. The pushes we see for Nakamura and Asuka may never come again. And that is why this moment in wrestling history is so important.

After the conclusion of the 2018 Royal Rumble, I'm even more excited to be attending WrestleMania 34. This will be the year two Asian wrestlers compete for WWE Championships in main event matches.

For me, that night will be deliver a deeply personal moment of pop because Asianness will have officially gained acceptance.

Follow the author of this article, Daniel Lee, on Twitter @Lee_Daniel721.